“The sky was of the thinnest, purest azure; spiritual life filled every pore of rock and cloud; and we reveled in the marvelous abundance and beauty of the landscapes by which we were encircled.”

John Muir, “Snow-Storm on Mount Shasta”

The sentiments associated with Muir’s religious naturalism are likely appreciated by those who climb mountains. Climbing can be exhilarating and gratifying, to say the least. But it can also be difficult, dangerous, scarry, etc. In climbing, as in life, adversity has the potential to disrupt our happiness and alter our perspective on things. Thoreau’s experience on Katahdin (described in my previous post) was so profoundly troubling that it led him to reject the notion that spiritual life can be found in the alpine. Muir’s report, in “Snow-Storm on Mount Shasta,” represents the counter extreme: in the presence of an immediate threat to his life, Muir never ceases to celebrate spiritual life among rock, ice, and clouds.

From Mt Shasta City

Muir’s Fiasco

It happened on his third, final ascent of Shasta, on April 30th, 1875. He was climbing with the experienced mountaineer and guide, Jerome Fay. The two were tasked with making barometrical observations on the summit.

Muir reports that before they reached the summit at 7:30am there was no discernible indication of an approaching storm. By noon, however, conditions had changed drastically, and Fay told Muir that if they did not descend immediately, they would get stuck on the summit. Muir, intent on making a 3pm observation, replied, “mountaineers can break down through any storm.”

A few minutes after 3pm and about a hundred feet below the summit the storm became “inconceivably violent,” and, faced with the extreme wind, snow, and cold, Fay thought it was impossible to proceed. The men were forced to retreat to the fumaroles (volcanic vents) at Sulphur Springs. Two feet of snow fell on the summit that afternoon and night. For seventeen hours, they lay flat on their backs among the scalding fumaroles. They were being frozen on their front sides and burned on their bottoms.

Extreme opposites frame Muir’s description of their experiences that night. Exhausted, hungry, and exposed, they were in a half-conscious state where “life is then seen to be a mere fire, that now smoulders, now brightens, showing how easily it may be quenched.” Yet as much as they suffered, Muir insists that their pain “was not of that bitter kind that precludes thought and takes away all capacity for enjoyment.”

Muir is not only put to the test physically; the snowstorm is an existential challenge to his belief that the mountains are his spiritual home. On a separate, earlier trip, after walking around the entire base of Shasta, a walk taking seven days and covering a hundred and twenty miles, Muir told the hostess of his hotel, “The mountains won’t hurt you, nor the exposure” (“A Conversation with John Muir”). Yet, on that night at Sulphur Springs, the mountains were hurting him. Muir’s reflection on the ordeal is both a concession that a life can easily be extinguished and a steadfast assertion of the “unflinching fair play of Nature, and her essential kindliness.” Throughout the ordeal, Muir sticks to his metaphysical guns: nature is kind, he says, and mountaineers are super strong: “Healthy mountaineers always discover in themselves a reserve of power after great exhaustion.” “It is a kind of second life only available in emergencies,” he writes, before telling of the three-thousand-foot descent to the warmth of base camp.

Our Trip

Thankfully our own trip to Shasta, May 31st to June 1st, went off without any comparable disaster.

I planned this trip with my brother for the principal purpose of scattering our grandmother’s ashes on the summit.

My brother also wanted to ski. I’m not an expert skier, and my hand-me-down AT gear is not particularly dialed. But I imagined what it could be to ski spring, corn snow, so I agreed to try it.

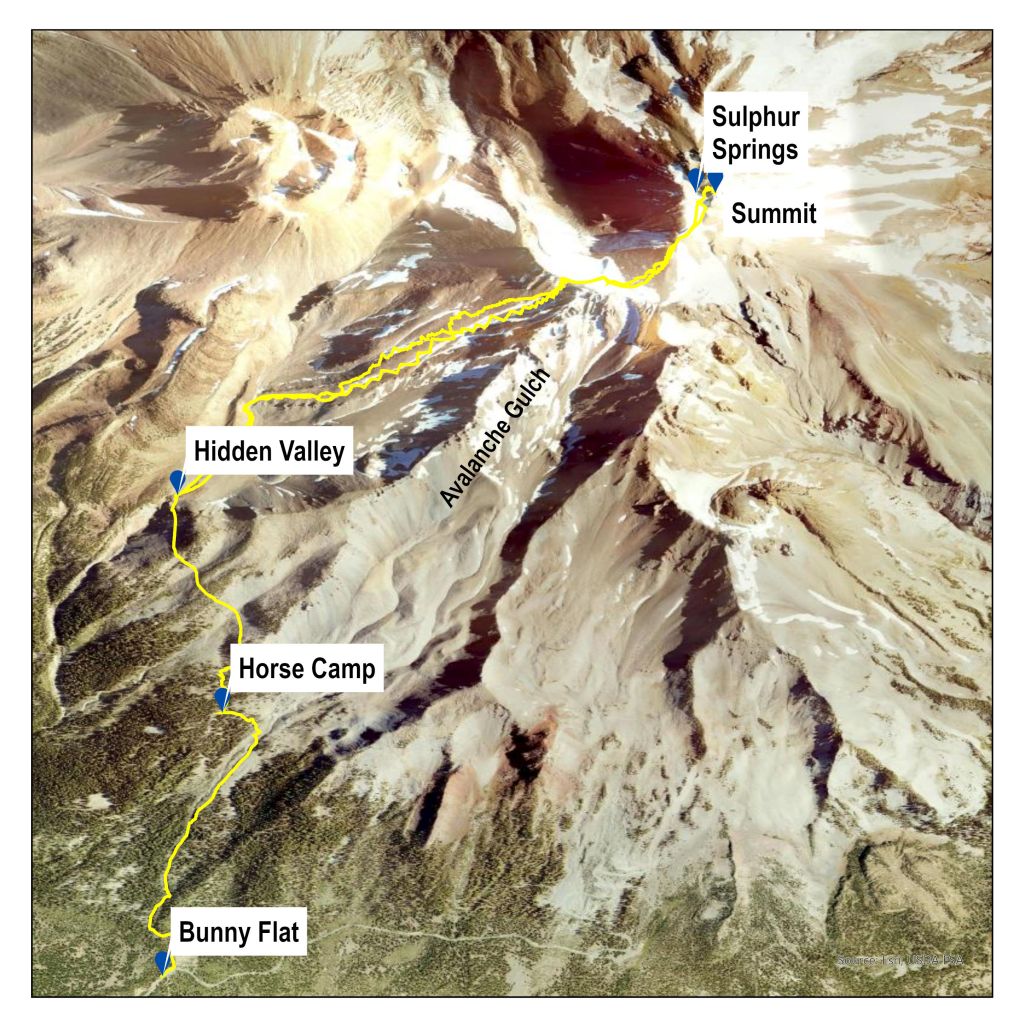

Muir’s favored plan would have been to start in Strawberry Valley (present day Mt Shasta City) ride to Horse Camp, and then, the next morning, make a direct line for the summit. Today, you drive to Bunny Flat. Other than that, Muir’s itinerary is pretty typical. Avalanche Gulch is the standard route.

This was my third time on Shasta, and the mountain seems more crowded nowadays than it was in the early 90s, on my first climb. On previous trips, I had taken the classic, Muir route. This time we chose the slightly less traveled Hidden Valley route.

The first day we skinned up about two thousand feet into Hidden Valley. We arrived at 4pm or so. The day was not difficult, but I already had blisters on my left foot from my improperly fitted ski boot. I wanted to test my skis in descent mode, so, after getting camp situated, we climbed a couple hundred feet and skied down for dinner. All seemed fine. An adventurous friend of my brother showed up just after dark, at about 9:30pm.

We woke up at 2:30am for a 4am departure. The sky was clear and calm. The overnight freeze firmed the snow up some, even at our elevation. We had roughly five thousand feet to climb in three miles. Shortly out of camp it gets steep, so we used crampons from the start and fixed our skis to our packs.

I felt bogged down by the ski equipment. The altitude didn’t help. At Misery Hill, about 13,000ft, the Hidden Valley and Avalanche Gulch routes merge, so we suddenly encountered climbing traffic. We ditched the skis, which was a relief. Just before the final summit push, the smell of sulfur reminded me to look for where Muir and Fay spent the night. The thought of lying down at that place, on those boiling puddles made Muir’s story hard to believe.

My brother and I waited for a break in the summit traffic. We reached the peak at 11am and released our grandmother’s ashes to the east, into a steady, light, westerly wind.

Ski mountaineering is largely an art of timing. For climbing, you want to go early, when conditions are firm, and get down before it warms up and the hazards (such as rock fall or afternoon storms) increase. For skiing, you want the snow somewhere in between ice and slush. The trick is to time the summit, so you transition from crampons to skis just as conditions change from those favoring climbing to those favoring skiing.

At the time we were ready to transition, I’d say conditions were pretty cruddy, a deeply chopped up and posthole-riddled mixture, subject to the late season freeze-thaw cycle. Some other skiers were hanging around, seemingly waiting for the snow to soften. My brother and his friend went ahead and dropped into the west face from the ridgeline, but not me. I couldn’t see past blowing the first turn, and the prospect of falling in that terrain wasn’t acceptable to me. A bit lower, I managed a few fun turns, but my ski descent mostly amounted to a lot of walking and bungling around with my equipment. As we descended, the snow got much softer, to the point that we triggered some sluffs, some very small wet loose slides, on a steep section above Hidden Valley camp. Below camp, travel was especially difficult because by then were carrying the additional weight of our sleeping and cooking stuff. I took a few tumbles skiing the glades and, at one point, got tangled in a tree. No pictures were taken during the seven-thousand-foot descent.

My skiing sucked! Yet if my story connects to the themes of Muir, it’s that my failed ski objective did not overshadow my capacity for enjoyment, and it certainly did not diminish the significance of our family summit ritual.

Perhaps the overarching themes of vulnerability, strength, and spiritual/ aesthetic experience are relatable to many mountaineering stories. Part of the charm of mountaineering is derived from the ability to artfully navigate the trying conditions of bare life. The problem with Muir’s story is that he exaggerates his abilities, as if mountaineers occupy a rank above mortals, like heroes in Greek mythology. Muir appears the hero of his own story. Although an incredible read, there is nothing courageous in Muir’s choice to weather the impending storm. The truth is he ignored Fay’s legitimate concerns for the sake of making scientific observations, a decision that put both of their lives at risk.

No doubt Muir’s ideas have been very important in the history of wilderness recreation and land preservation. However, it is hard to see the wisdom in Muir’s consoling mountain metaphysics or in his confidence in the “second life” power of self-rescue. To me, the danger and beauty of the mountains is bound to be paradoxical. In a sense, when Thoreau grappled with this same problem, he got closer to the truth: mountain tops are unfit for human life. And yet, what better place to confront nature’s mystery, above it all, exposed, and at the limit!

Sources

(1906, November). A Conversation with John Muir. World’s Work, 8249-8250.

(1877, September). Snow-Storm on Mount Shasta. Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, 55 (328), 521-530.

Leave a comment