“The tops of mountains are among the unfinished parts of the globe, whither it is a slight insult to the gods to climb and pry into their secrets, and try their effect on our humanity. Only daring and insolent men, perchance, go there…Pomola is always angry with those who climb to the summit of Ktaadn” (Thoreau, Ktaadn, 73).

Well before I set foot on Katahdin, I had read Thoreau’s essay, Ktaadn, and I was both intrigued by his account of the climb and puzzled by its implications for his wilderness philosophy. It is commonly believed that Thoreau, as an American transcendentalist like John Muir, looked to wild nature for spiritual resource. In fact, Muir’s famous “…wildness is a necessity…and mountain parks…fountains of life…”(Our National Parks, 459) seems to echo Thoreau’s words:

“Life consists with wildness. The most alive is the wildest. Not yet subdued to man, its presence refreshes him” (Walking, 665).

No doubt, Thoreau imagined wilderness recreation to be spiritually gratifying, and his imagination moved him to explore the backwoods of Maine and its highest mountain. Thoreau writes that travel in the direction of the wild and unsettled portion of mountainous Maine “…will carry the curious to the verge of a primitive forest, more interesting…than they would reach by going a thousand miles westward” (Ktaadn, 6).

On the 31st of August 1846, he left Concord for Katahdin, yet when he finally arrives on the mountain, he is profoundly troubled. Thoreau paints a savage and chaotic picture of the alpine landscape—a picture that presents a challenge to the wilderness of his imagination. For me, Thoreau’s story of his climb enriched the geography of Katahdin, and my own summit attempt cast fresh perspective on Thoreau’s narrative.

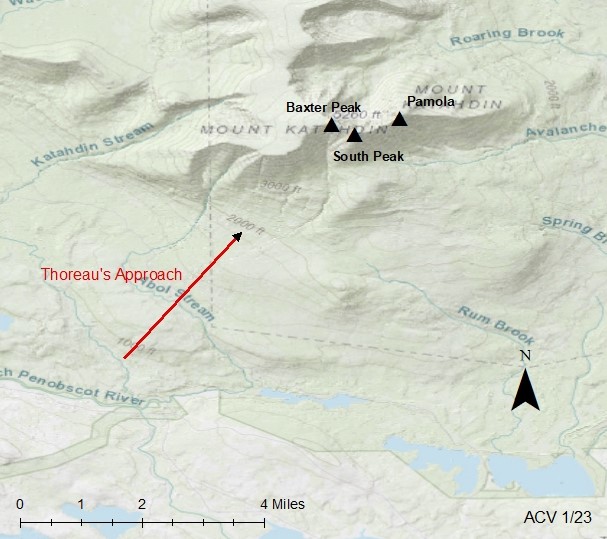

Katahdin is remote, and less developed and accessible than other northeast mountains. It took Thoreau a day to get from Concord to Bangor by train and steamboat and then nearly a week to travel by horse and wagon and boat (batteau) up the Penobscot River to its West Branch and eventually to the mouth of the Aboljacknagesic stream, “open-land stream” (Ktaadn, 63), where he camped before the climb.

In contrast, it took my brother and I ten hours to drive from Syracuse to Millinocket. Interestingly, our route from Bangor to the trailhead roughly paralleled Thoreau’s travels along the watercourse: highway 95 runs along the Penobscot River; 157 follows West Branch Penobscot; and the road leading to our trailhead, the Golden Road, leads to Abol (short for Aboljacknagesic) bridge, which is close to where Thoreau camped on September 6th, 1846.

Our Climb

The day after Christmas, 2022, my brother and I met my mountaineering friends in Millinocket.

Our planned route to the summit was from the basin on the east side of the mountain. We wanted to take the Dudley Trail from Chimney Pond and complete a loop, clockwise, traversing the Knife Edge to Baxter. In the summertime, one can drive all the way to Roaring Brook Camp, but, since we climbed in winter, when Roaring Brook Road is closed, we had to walk or ski thirteen miles from Abol Bridge to Roaring Brook. We had four days–one night at Roaring Brook and two at Chimney Pond.

We were the first visitors of the ’22-’23 winter season. At this early date, the southern aspect, low-elevation slopes had very little snow cover, so we carried our skis on Abol Stream Trail and until we reached Roaring Brook Road.

Generally, above Roaring Brook, snow conditions consisted of a weak, two-to-three-inch crust over about twenty inches of powder. Nonetheless, navigation was not a problem, and we only had three miles to cover on our second day to Chimney Pond. The bunkhouses in the winter are luxurious. They come supplied with firewood, and the one at Chimney Pond gets downright hot.

On summit day, above Chimney Pond, navigation on the Dudley trail got much more challenging. This was compounded by the fact that the trail had been re-routed, and our maps, both paper and digital, did not agree with the blue blazes on the rocks (often covered by ice or snow) or the trees (growing less dense as we climbed). Route-finding difficulty, snow conditions, and the steep terrain slowed our pace to a discouraging two hours per mile. At about 10:30am, above timberline, the wind picked up and drove us to shelter behind a large pyramidal boulder in order to change our snowshoes for crampons and ice axe.

Thoreau’s Approach

Thoreau’s course began the same way as ours, by following the Abol Stream, but our paths shortly diverged. Thoreau was aware that the mountain may be more easily approached from the east side, but he wanted to see more of the wilderness, so he chose a more direct approach.

His compass pointed northeast to the summit, and his path led “…parallel to a dark seam in the forest, which marked the bed of a torrent, and over a slight spur, which extended southward from the main mountain…” (Ktaadn, 64). He later says that on the 7th of September, his party turned west to the torrent to establish camp near a water source. That day he scouted the route above solo, going up a deep, narrow ravine at an angle of forty-five degrees (67). He returned to camp, and the next morning the party started up the ravine, this time aiming for the right hand, highest peak (70).

Thoreau ended up leaving his companions for the summit. It is impossible to know exactly where he was, but he does say that he “…reached the summit of the ridge…” (71).

Summit Reflections

Here is Thoreau’s puzzling picture of the landscape of the summit ridge:

“It was vast, Titanic, and such as man never inhabits. Some part of the beholder, even some vital part, seems to escape through the loose grating of his ribs as he ascends. He is more lone than you can imagine. There is less of substantial thought and fair understanding in him, than in the plains where men inhabit. His reason is dispersed and shadowy, more thin and subtle, like the air. Vast, Titanic, inhuman Nature has got him at disadvantage, caught him alone, and pilfers him of some of his divine faculty” (72).

On this view, mountaintops are hardly happy, hospitable places that provide nourishment for the soul; on the contrary, the alpine robs human beings of understanding and spirituality and leaves them feeling weak and alone. In the span of a few pages, Thoreau contradicts the basic tenants of American transcendentalism and dismisses many of its popular metaphors for wild nature: “…here is no shrine…” (72); “[H]ere was no man’s garden…not his mother Earth…” (79).

Katahdin’s northern location, isolation, prominence, and rugged profile does provide a unique mountaineering experience in the northeast. For Thoreau, this would have been a novel experience, introducing him to a landscape unlike anything he had seen. Leaving his companions behind, he arrived on the ridge literally alone, with minimal equipment to minimize the risk. The late summer clouds, wind, and exposure were enough to make him feel out of his element.

Remarkably, Thoreau’s story of alien landscape is not restricted to the summit ridge. Speaking of the so called “Burnt Lands,” a low-elevation, grassy area on the descent, he writes, “Perhaps I most fully realized that this was primeval, untamed, and forever untameable Nature…Nature was here something savage and awful, though beautiful” (78-79).

With respect to Katahdin’s alpine landscape, I believe that what Thoreau is failing to appreciate is the sublime, the aesthetic feeling of all-powerful nature. One of the most systematic and influential thinkers on the subject, Immanuel Kant, speaks of mountains as sites of delight in the face of the fearful. But Kant goes on to explain that the experience of the sublime—the feeling of increased strength and courage to test ourselves against the power of nature—requires some assurance of safety. Sublime landscape is lost on someone in the grip of fear (Critique of the Power of Judgment, 144-145). Perhaps this is why Thoreau sees only danger and disarray on the summit ridge; he is simply afraid.

I admit that when the wind picked up on Pamola and threatened my balance, with momentary pause, Thoreau’s statement that the mountain is cursed crossed my mind. In the final analysis though, Thoreau only sees the awful aspect of alpine landscape. Mountaineers acknowledge the feeble capacity of humans to withstand nature’s power; yet as long as we find ourselves safe, we are capable of experiencing more than debilitating fear. So, after preparing ourselves for the changing summit conditions, when we stood up in the wind, we were invigorated as we continued up Pamola. Perhaps the feeling of the sublime in that circumstance is borderline insolent or hubristic. We felt great, but we agreed that continuing onto the Knife at that time would have pushed our luck too far.

Sources

- Kant, Immanuel. Immanuel Kant: Critique of the power of judgment. Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Muir, John. John Muir: the eight wilderness discovery books. Diadem Books; Mountaineers, 1992.

- Thoreau, Henry D. Ktaadn. Tanam Press, 1980.

- Thoreau, Henry D. “Walking.” Atlantic Monthly, vol. 9, no. 56, 1862, pp. 657-674.

Leave a comment